When Archives Become Weapons: The Destruction of Palestinian Memory

What happens when a people’s ability to prove they exist depends on documents that are systematically destroyed? For Palestinians, this isn’t hypothetical—it’s been reality for 77 years. From the looting of 70,000 books during the 1948 Nakba to the obliteration of Gaza’s entire archival infrastructure in 2023-2025, the destruction of Palestinian archives reveals something fundamental about how power operates through control of memory.

This isn’t just about lost papers. It’s about families unable to prove land ownership, students who can’t attend university because they legally “don’t exist,” and young people transforming smartphones into archives because physical repositories keep burning.

When the Library Becomes a Battlefield

The pattern begins with a “salvage operation.” In April-May 1948, as Palestinians fled West Jerusalem, the Jewish National and University Library conducted what it termed a systematic collection effort. Israeli scholar Gish Amit’s research documents the reality: at least 30,000 books were looted from Palestinian homes in West Jerusalem alone, with total losses reaching 70,000 books.1

Among the seized collections was educator and Palestinian Christian, Khalil Sakakini’s, entire private library. He mourned in his diary:

Farewell, my library! Farewell, the house of wisdom, the abode of philosophers, a house and witness for literature! How many sleepless nights I spent there, reading and writing, the night is silent and the people asleep…goodbye, my books! I know not what has become of you after we left: Were you looted? Burnt? Have you been ceremonially transferred to a private or public library? Did you end up on the shelves of grocery stores with your pages used to wrap onions?2

Image: Khalil Sakakini and his family behind the house of Sakakini at the Katamon Neighbourhood in Jerusalem, prior to their expulsion.3

Image: Khalil Sakakini and his family behind the house of Sakakini at the Katamon Neighbourhood in Jerusalem, prior to their expulsion.3

His books ended up at Hebrew University’s library, stamped “AP” for “Abandoned Property”—a designation still visible today. Approximately 50,000 rare manuscripts from 56 libraries in and around Jerusalem remain unaccounted for.1

The destruction accelerated exponentially in 2023-2025. All of Gaza’s 12 universities were destroyed or severely damaged, along with at least 11 major libraries, 12 museums, and 8 publishing houses.4

The Gaza Central Archives, containing 110,000 historical documents dating back 150 years, was deliberately destroyed by Isreali forces in late 2023. Mayor Yahya al-Sarraj stated: “These documents, dating back a long time, were burned, turning them into ashes, erasing a large part of our Palestinian memory.”4

Image: The area housing the Gaza Central Archives after bombing by Israeli forces.5

Image: The area housing the Gaza Central Archives after bombing by Israeli forces.5

The Invisible People: When Records Control Existence

Here’s where it gets truly Kafkaesque. Since 1967, Israel has maintained complete control over the Palestinian population registry—the computerized database that determines who legally exists.6 Since 2000, Israel has largely frozen processing of family reunification applications, address changes, and most registry updates, creating what Human Rights Watch calls “hundreds of thousands” of affected Palestinians living in legal limbo.

The State of Being Stateless

Wael Kawamleh, born in 1962, was able to retain his ID number, but his wife and children were denied. His children, Fayez and Khulood, born in 1973 and 1975, were denied in 2003 and 2004 respectively, and have no status anywhere.6

I left everything to hold onto my ID and what did we get back? No IDs for two of my kids and no visa for my wife, meaning they can’t work or move freely. —Wael Kawamleh6

In 2015, every single Palestinian in the West Bank who applied for ID numbers was denied.6

Meanwhile, approximately about two-thirds of West Bank land (≈62-70%) remains unregistered, making it vulnerable to Israeli declaration as “state land” to justify settlement expansion. Israeli Military Order 291 in 1968 stopped all land registration processes. The current registration process is so complex that one Palestinian land professional’s flow chart spans “three sheets of legal-size paper.”7

For more info on the registration of land in Palestine, see B’Tselem’s “Conquer and Divide” map.

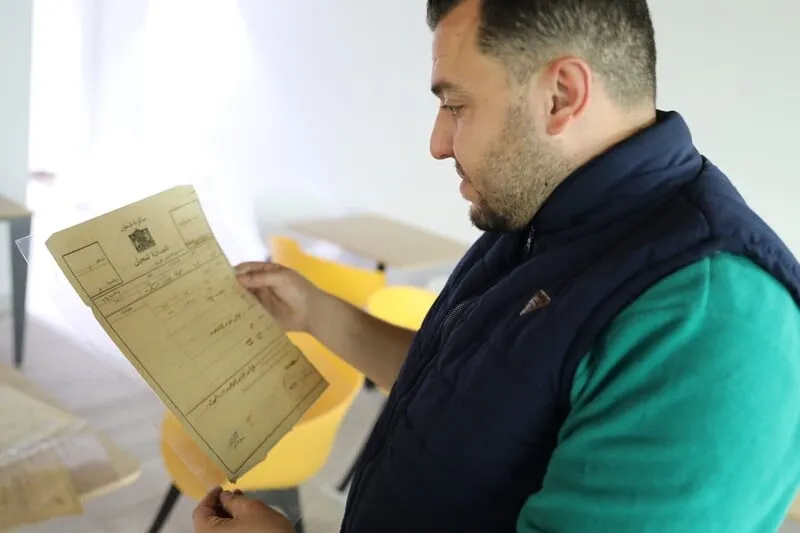

Yet families guard their Ottoman-era and British-era deeds like talismans. Adam al-Madhoun in Gaza inherited his grandfather’s British-era deed to a 37-acre farm:

These documents prove that Palestinians owned the land. They refute Israel’s claims that Palestine was empty…how we have preserved these documents to this day and how we will hand them on to our sons.7

The documents provide no remedy. But they provide proof—of ownership, of existence, of a past that someone desperately wants erased.

Image: Adam al-Madhoun with his grandfather’s British-era deed. (Mohammed Al-Hajjar)7

Image: Adam al-Madhoun with his grandfather’s British-era deed. (Mohammed Al-Hajjar)7

Digital Resistance: When Smartphones Become Archives

Young Palestinians have transformed social media into powerful documentation tools, creating what scholars call “digital sumud” (steadfastness)—asserting Palestinian existence through real-time recording when physical archives are destroyed.

Gaza photojournalist Motaz Azaiza’s Instagram followers grew from 25,000 before October 7, 2023, to over 18 million by January 2024—making him one of the most-followed witnesses to conflict in history.8 When asked what he wished the world knew about Gaza, he responded simply: “That we’re human.”

Other prominent documenters include Bisan Owda (3.8 million followers), Hind Khoudary (1+ million), and Plestia Alaqad (4.7 million). As Plestia explained:

“As a Palestinian living in Gaza, you don’t have a choice but to be a war journalist. Overnight, your life changes…It’s not about me as Plestia. It’s about me as a Palestinian.”8

The documentation comes at extreme cost. At least 80 journalists were killed in the first three months of the Gaza conflict—the deadliest period for journalists since tracking began in 1992.8 Mohammed Halimy, whose “Tent Life” series gained hundreds of thousands of followers, was killed in an Israeli airstrike in August 2024 while at an internet café.

The documentation also faces systematic suppression. Palestinian digital rights organization 7amleh documented over 5,100 cases of censorship between October 2023 and September 2024.9 The Israeli government’s Cyber Unit sent 9,500 content takedown requests, achieving a 94% compliance rate—operating without court orders.9

Despite this, Motaz Azaiza was named TIME’s 100 most influential people of 2024, nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, and won France’s Freedom Prize. Social media documentation has transformed into bearing witness that reaches audiences far beyond traditional journalism’s scope.

The Race to Digitize What Remains

While young people document with smartphones, formal institutions race to preserve what physical materials still exist. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, launched in 2018 with a $3.8 million grant, has digitized 343,485 items across 416 collections.10

International collaborations include UCLA Library’s International Digital Ephemera Project, Columbia University’s Center for Palestine Studies maintaining 40 Palestinian village memorial books, and UNRWA’s archive—recognized by UNESCO’s Memory of the World program—containing 430,000+ negatives, 10,000 prints, 85,000 slides, and 75 films.10

As Palestinian Museum project coordinator Majd Al-Shihabi explained:

“A second Nakba is happening slowly right now, and it will be complete when the last person [who lived] during the Nakba will no longer be with us. A big part of this push toward archiving is the nagging awareness that we have an entire generation of people we are losing, and with them all that memory and knowledge.”10

Yet digitization cannot replace physical preservation. Original documents provide evidentiary value for legal claims and war crimes prosecution. Material artifacts embody cultural practices in ways that defy digitization. Both are essential: physical archives for authenticity and legal standing, digital for access and survival when physical repositories face destruction.

Image: The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive Collections.10

Image: The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive Collections.10

Understanding Archival Violence

The systematic destruction of Palestinian archives exemplifies what archival theorist Randall C. Jimerson calls archives as “technologies of rule”—not neutral repositories but instruments of control.11 The concept of “archival silence” applies with particular force: these aren’t passive gaps but actively produced absences resulting from deliberate destruction and concealment.

To learn more about archival silence, see our blog post The Politics of Preservation.

How silences happen:

- Bureaucratic visibility favors the powerful: Governments generate thick paper trails; grassroots groups leave thinner traces

- Documentation follows resources: Preservation takes money, space, and staff

- Description encodes perspective: The same record can highlight “revitalization” or document displacement

- Access isn’t equal: “Open” records can be practically closed through paywalls or limited hours11

Scholar Nur Masalha introduced the term “memoricide”—the intentional killing of memory—to Palestinian studies, arguing it’s “an aspect of cultural genocide” and “related to supersessionism, itself an aspect of settler colonialism.”12 This framework helps explain why Israel has destroyed not only archives but all 12 universities in Gaza, 95% of schools, 1,109 mosques, and the world’s third-oldest church—targeting the entire infrastructure of Palestinian memory and cultural transmission.

What This Means for Family History

The destruction of Palestinian archives reveals something fundamental: official records are never neutral. What gets kept, how it’s described, and who can see it are all human choices tied to power.

For those thinking about how families preserve stories, the Palestinian case teaches critical lessons:

- Official records serve administrative needs first: When we treat official documents as inherently more “true” than oral histories, we’re privileging state power over lived experience

- Silences are structural, not accidental: When you can’t find records of your ancestors, ask why. What systems prevented their documentation?

- Multiple sources matter more than ever: Pair “official” documents with community memory and personal ephemera

Why Multimedia Evidence Matters

This is where Oracynth’s mission becomes more than technical architecture—it’s an ethical stance about what counts as legitimate historical evidence.

Traditional genealogy software, shaped by institutions focused on proving lineage for legal and religious purposes, creates a hierarchy where birth certificates are “real” evidence while oral histories and photographs are decorative “attachments.”

But what happens when birth certificates can’t be registered? When land deeds are seized? When archives are bombed? When the most vulnerable communities—refugees, diaspora populations, those whose relationships aren’t recognized by the state—have their paper trails systematically erased?

Their stories don’t become less true. The evidence just looks different.

Oracynth’s assertion-aware data model treats oral interviews, family photographs, and personal documents as first-class source materials alongside traditional vital records. The young Palestinians documenting their lives on Instagram aren’t amateur hobbyists—they’re creating the historical record when official archives burn. The families guarding Ottoman-era land deeds aren’t being sentimental—they’re maintaining proof of existence when legal systems deny their registry.

When we build archival systems that privilege certain types of evidence over others, we’re making political choices about whose stories matter. This matters especially for:

- Immigrant communities whose documentation was lost during displacement

- Families whose relationships aren’t legally recognized in historical records

- Communities whose knowledge preservation traditions center on oral transmission

- Anyone whose existence doesn’t fit neatly into state bureaucracies

Memory as Resistance

The most profound lesson from Palestinian archival resistance: memory itself is an act of defiance against erasure.

Image: A view of destroyed buildings in Gaza City on October 25, 2023. Ali Jadallah / Anadolu / Getty 13

Image: A view of destroyed buildings in Gaza City on October 25, 2023. Ali Jadallah / Anadolu / Getty 13

When Motaz Azaiza declares “the world is watching my home through my lens,” when families guard century-old land deeds as their “most treasured possessions,” when young people risk death to document their own displacement—they enact what memoricide attempts to destroy: the assertion that Palestinians existed, exist, and will continue to exist.

This is not unique to Palestine. Every community whose history has been marginalized knows this truth: preserving your own story is resistance. Telling it on your own terms is power.

While Oracynth is just one small tool in a vast ecosystem of preservation efforts—from the Palestinian Museum’s digitization work to academic archives to community documentation projects—we’re committed to building infrastructure that serves families whose stories have been systematically devalued by traditional tools.

Everyone deserves the ability to document their existence.

Everyone deserves tools that treat their evidence with respect.

Everyone deserves to pass their stories to the next generation—in whatever form those stories take.

We’re building technology that acknowledges reality: family history exists in many forms, official records aren’t neutral, and the most important stories are often the ones that existing systems weren’t designed to preserve.

Preserve Your Family's Truth

Every family has stories worth preserving—whether they're in official documents, old photos, or the memories passed down through generations. Build an archive that honors all forms of your family's truth.

Free early access • No credit card required

cover image: Gaza’s Main Public Library, destroyed by Israeli forces in 2023.14

Footnotes

-

Gish Amit, “Ownerless Objects? The Story of the Books Palestinians Left Behind in 1948,” Jerusalem Quarterly 33 (2008). Full text (Institute for Palestine Studies) ↩ ↩2

-

Georgetown University, “Scholasticide in Gaza: Israel’s Continued Colonial Policy of Eradicating Palestinian Knowledge” (2024). Article; See also Khalil Sakakini’s diary ↩

-

The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, The Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center Collection, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center Sub-collection 1: Photographs: Khalil Sakakini, Mousa al-Alami and their Families ↩

-

PEN America, “All That is Lost: The Cultural Destruction of Gaza” (2025). Report; see also UNESCO Damage Verification Reports. ↩ ↩2

-

AA.com.tr: Isreal destroyed Central Archives of Gaza City ↩

-

Human Rights Watch, “Israel: Jerusalem Palestinians Stripped of Status” (2020). HRW Report ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

“Deeds of the displaced” (2021). Article; see also B’Tselem’s “Conquer and Divide” map. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Committee to Protect Journalists, “Journalist Casualties in the Israel-Gaza War” (2024). CPJ Database; also see TIME 100 Most Influential People of 2024, “Motaz Azaiza” (Feb 2024). Article ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

7amleh - Arab Center for Social Media Advancement (2024). Website; Human Rights Watch, “Meta’s Broken Promises” (2023). HRW Report ↩ ↩2

-

Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, Project site; UNRWA, Photo and Film Archive ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Randall C. Jimerson, “Embracing the Power of Archives,” American Archivist 69:1 (2006). Article (JSTOR) ↩ ↩2

-

Nur Masalha, “Settler-Colonialism, Memoricide and Indigenous Toponymic Memory: The Appropriation of Palestinian Place Names by the Israeli State” (2015). doi.org/10.3366/hlps.2015.0103 ↩

-

Lithub, 2023: Gaza’s main public library has been destroyed by Israeli bombing. ↩