Beyond Blood: FAN and the Future of Family History

Genealogy gives us tools to understand the dead—but too often those tools are biased toward blood and law, ignoring many of the relationships people actually lived: godparents, neighbors, mentors, chosen family.

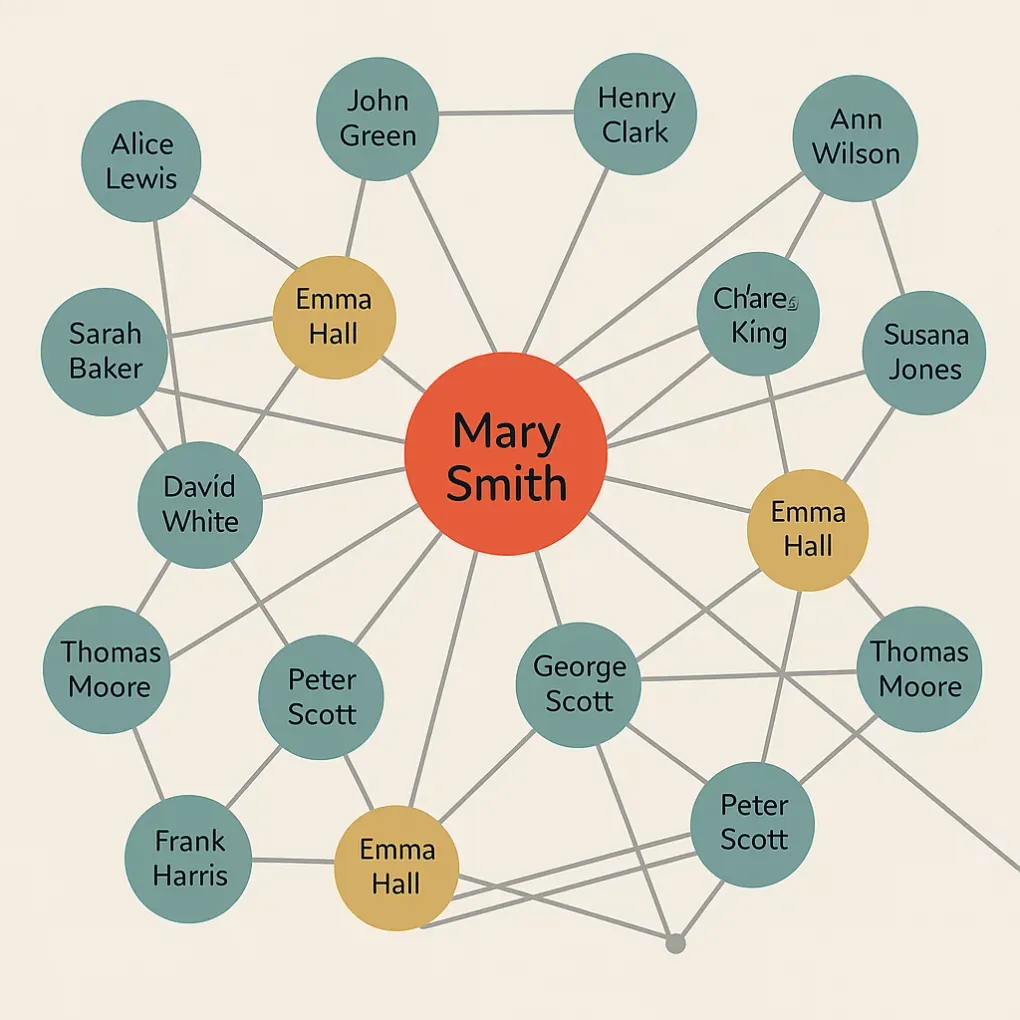

The FAN principle—Friends, Associates, Neighbors—was a breakthrough. It proved that if you widen the lens from pedigree to community, you can solve identities that once seemed impossible.

FAN also exposes the limits of our current systems: we still don’t treat social and chosen ties as first-class data, just means to an end where blood and law are ultimately the goal. That’s the next frontier in family history.

From pedigrees to communities

For much of its history, genealogy relied on consanguineal kin (blood) and affinal kin (marriage). Records of births, marriages, and deaths formed the backbone. If those failed, the trail often went cold.

The FAN approach, named and popularized by Elizabeth Shown Mills, widened the circle. When direct evidence is missing, study the cluster: neighbors, associates, and witnesses. People appear together on census pages, in pew rolls, in land transactions, on militia rosters. The cluster often gives you valuable insight into who your subject really was.1

Marsha Hoffman Rising demonstrated FAN’s full power in Opening the Ozarks, tracing thousands of settlers through community context rather than pedigrees alone. Her project made clear: communities unlock identities that lineages alone cannot.23

Naming more kinds of kin

To make sense of what FAN reveals, we need the right vocabulary. Anthropology reminds us that kinship isn’t just blood and law:

- Consanguineal kin — by descent (parents, children, siblings).4

- Affinal kin — by marriage (spouses, in-laws).5

- Ritual/spiritual kinship — created by rite or office, such as compadrazgo (godparenthood).67

- Chosen/social kin (sometimes called “fictive” kin) — enduring ties forged by care and obligation, like queer “chosen families” or honorary aunts and uncles.8

If our words for kin are broader, our software ought to be too.

Why the tools lag behind

Some genealogy programs have tried to reflect FAN’s insights:

- RootsMagic 9 “Associations” lets you record associates, but analysis is thin.9

- Family Historian allows “witnesses/shared events,” attaching non-principal participants—but the model is still event-centric, not network-centric.10

- Clooz “Composite View” visualizes people-document networks, but stops short of durable, typed relationships.11

These features are useful, but they highlight the gap. Researchers want to record networks, and the software only half supports them.

Think of it this way: a “two-hop network” is just friend-of-a-friend connections; a “role-rich model” means a person can appear as witness, executor, juror, pew neighbor—not just spouse or child. These aren’t abstractions; they’re what genealogists already trace by hand. Our tools just don’t yet treat them as central.

Seeing care as part of family history

Christine Sleeter’s work on critical family history reminds us that families live inside structures of race, class, gender, and colonization.8 Those forces shaped whose ties were documented and whose were erased.

Queer chosen families, ritual godparent ties, neighbor care networks—these are often missing from the official record, yet they structured real lives. Software that doesn’t model them risks reproducing those silences.

Walking through the door FAN opened

- FAN showed us how communities solve genealogical puzzles.

- Critical history reminds us that fictive kin is often more important than blood and law to a subject’s identity.

- Future genealogy must model all types of kin and preserve them as first-class data.

FAN opened the door. To tell fuller histories, our models and tools need to walk through it.

Join the work of widening family history

Help build archives and tools that reflect real human networks.

Free early access • No credit card required

Footnotes

-

Elizabeth Shown Mills, “QuickLesson 11: Identity Problems & the FAN Principle,” Evidence Explained. https://www.evidenceexplained.com/content/quicklesson-11-identity-problems-fan-principle ↩

-

Marsha Hoffman Rising, Opening the Ozarks: First Families in Southwest Missouri, 1835-1839 (Derry, NH: American Society of Genealogists, 2005), 4 vols. Project overview: https://www.marsharising.com/Opening%20the%20Ozarks/First%20Families%20of%20SW%20MO.htm ↩

-

FamilySearch Catalog, “Opening the Ozarks,” confirming publication details and extent. https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/catalog/1326260 ↩

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Consanguinity.” https://www.britannica.com/summary/consanguinity ↩

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Affinity (kinship).” https://www.britannica.com/topic/affinity-kinship ↩

-

Oxford Reference, “Compadrazgo.” https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095628441 ↩

-

Roland Armando Alum, “The Continuing Relevance of Compadrazgo: Spiritual Kinship in Latin America,” Anthropology News, Jan 3, 2024. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/the-continuing-relevance-of-compadrazgo-spiritual-kinship-in-latin-america/ ↩

-

Christine Sleeter, “Critical Family History: An Introduction,” Genealogy 4, no. 2 (2020). https://www.mdpi.com/2313-5778/4/2/64 ↩ ↩2

-

RootsMagic Team, “Exploring the New ‘Associations’ Feature in RootsMagic 9,” RootsMagic Blog, Jul 20, 2023. https://blog.rootsmagic.com/?p=3687 ↩

-

Family Historian, “Witnesses (Shared Events)” — Help, v7. https://www.family-historian.co.uk/help/fh7/witnesses.html ↩

-

Clooz, “A Unique Analysis Tool: Composite View.” https://clooz.com/composite-view/ ↩